#05: Athlete's data and the thorny question of ownership

Like top trumps on turbo mode, athletes now carry a dataset on their shoulders that stands to be one of the most valuable properties in sport. Can it be done equitably?

A quick reminder.

I’m Andrew. I was an Olympic athlete, then I moved into building health tech businesses. I’ve built and exited two businesses over the last 10 years: Bootstrapping our first business in 2013 through to acquisition, then helping lead the EMEA half of a global health and diagnostics business through to IPO on the Nasdaq in 2022. Now I’m onto my next venture.

I write about stuff (very) intermittently. Generally about businesses and technologies that I find exciting, at the intersection of sport, health and nutrition - I call this Human Performance Tech.

First things first, it’s been a while.

As with all things, creating content is powerful only through consistency - something I’ve lacked with this newsletter. That being said, in the past 6 months I bought a small, but very cool, supplement business in the US (www.meetaila.com) and co-founded a new, ambitious digital health venture (www.stridehealthgroup.com) More about these another time.

Oh, and I just had a second child.

Oh, and I just moved to Portugal.

So go easy on me.

Anyway, what do we all do in the middle of the night while walking a newborn around?

That’s right…

We write about athlete data rights!

Data isn’t the new oil in sport… It’s far more valuable.

If you enjoy watching sport, you’ve been benefitting from organisation collecting data about sportspeople your entire life. Athlete data is nothing new, it was just pretty rudimentary:

How many tries has that player scored?

How tall is that sprinter?

How many surprising post-sport careers as Editor-at-large for Monocle magazine does that Japanese talisman hold? (Answer: My second favourite post-sport pivot from Hidetoshi Nakata, after Flamini’s biochemistry turn)

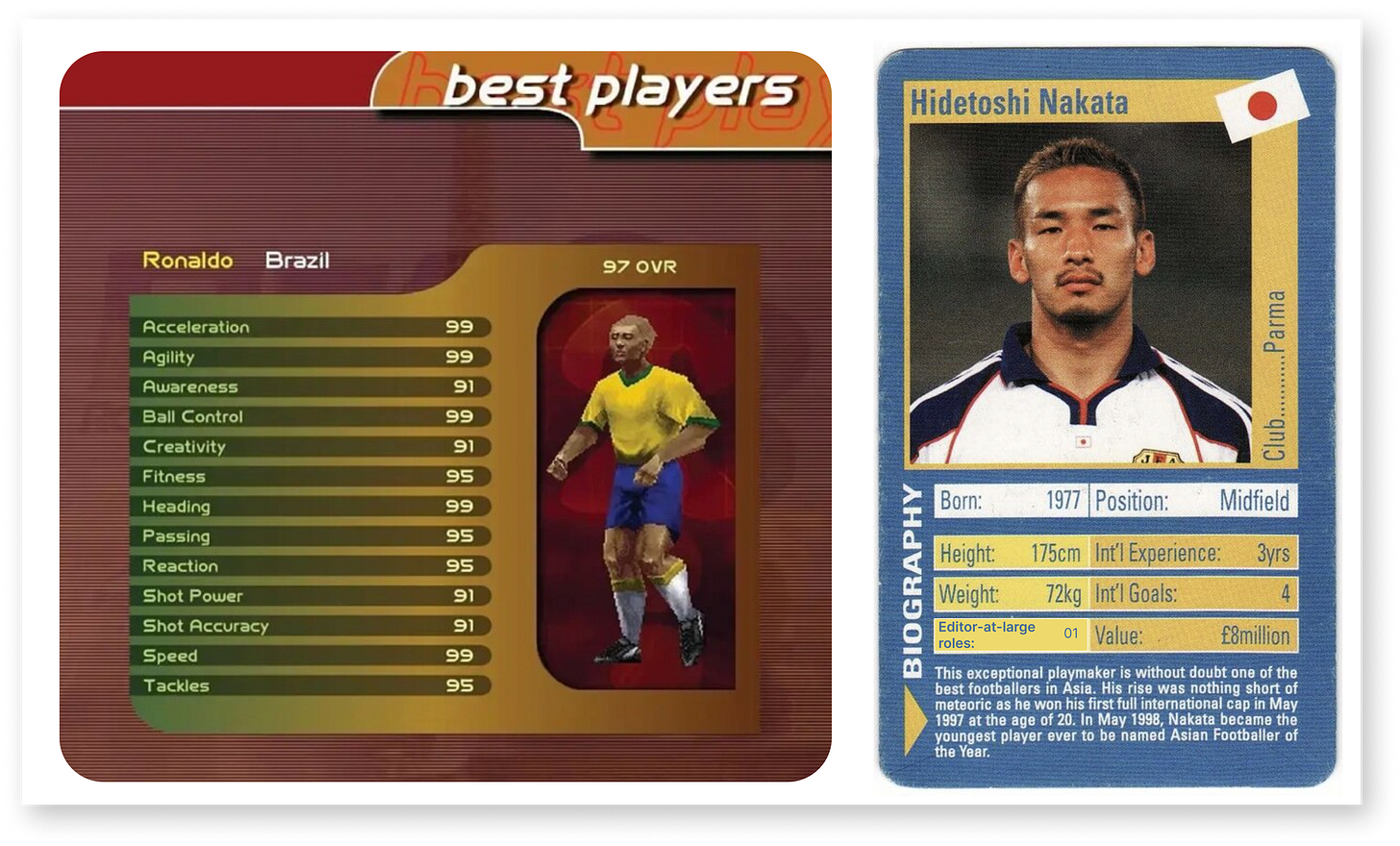

This data informed pretty basic use cases - rankings, team selection on the performance side, and rudimentary marketing assets (top trumps, player qualities on early ISS and Fifa) and in some cases on the product side (Tennis introduced the serve speedometer gun in 1989.)

Just a few years ago, athlete data was so basic, it didn’t matter who owned it.

Now it does.

Back in September, I took part in a debate for the Sports Technology Group at Lords Cricket Ground. In a surprisingly Oxbridgian set up, myself and three esteemed colleagues from the world of sport were set the task of putting forward a case either for or against the motion “OWNERSHIP OF ATHLETE DATA SHOULD REMAIN THE PROPERTY OF THE ORGANISATION COLLECTING IT”

Unsurprisingly, I was making the case against this motion. I.e. The athlete should have ownership of this data.

Supporting me on team against was sports agent supremo Tim Lopez, and fighting BITTERLY against the motion were pre-eminent sports lawyer Andy Dawson and legendary MD of StatSports (as mentioned in my last newsletter), Paul McKernan.

It’s temptingly easy to jump to what seems like a quick and clear answer. If you’re an athlete it’s obvious, and if you’re on the other side of the table, it’s also obvious.

Or so you think.

I came in to the debate with an extremely clear idea in my head and could not grasp how on earth anyone could make the argument that athletes shouldn’t own their data in entirety. But just like everything in life, once you leave your echo chamber, there’s nuance beyond the border.

It was genuinely eye opening to hear the other perspective, and it raises a number of legitimate questions that sport absolutely must answer for long term survival of the ecosystem.

A new paradigm in athlete’s rights

Historically, data sets have focused exclusively on publicly available and mainly obvious data. In order to think about the nuances of the argument, I think it’s important to try place the types of data we’re talking about into three buckets:

1 - Publicly available, non-sensitive data

On the viewing side in football and some other sports, a number of technologies like video tracking gave statistics-keen fans and bookies a remarkable data set. Services that track and quantify this have sprung up all over the sports eco-system.

This data might be obvious; passes completed, personal best time, even games won for example. It also might be slightly less obvious, like distance covered during a match.

The mechanisms for collecting this data can be relatively difficult, but in these cases, due to the public nature of the data I doubt there have been many objections to the notion that the organisation collecting this may also own (and monetise) this. To me this is clear cut - the athlete doesn’t need to own this data.

I do however believe they should have a say in its use, e.g. a player whose religion dictates against gambling should be able to opt out of their data, even if publicly available, being used by bookies.

2 - Obviously personal and sensitive data

This is traditionally biometric data; heart rate, VO2 max. It could even be medical data; injury status, blood chemistry and other lab tests etc.

This is even clearer. There are obvious legal frameworks, safety guards and personal data standards as to the ownership and rights to this data - it should belong and be the express right of the athlete as to how this gets used, if at all.

(Here’s my thoughts on the potential upside for athletes in this data from newsletter #04)

3 - Potentially sensitive, hard-to-interpret but publicly available data.

Here’s where it gets tricky.

I don’t know what to call this type of dataset, this is new ground. I’m thinking about how conclusions could be inferred from publicly available data to potentially conclude sensitive data or performance advantage - a use case which is largely only possible due to the recent accessibility of large data modelling (aka ChatGPT-like services).

This one requires a little more detail.

Let’s take where a tennis champion places their second serve as an example. Readily available data can tell us where they tend to place this serve, the average speed and how often they double fault - fine. Not too much to see here.

But let’s say you then feed an entire playing career data of seconds serves for that player into a model, then you overlay every other possible variable; how far into the game, current score, weather conditions, time of day, noise of crowd, rest days since last match, prize money on the line, media about the player’s personal life, etc etc

Could we start to infer conclusions or predictions about that player’s chance of success that could be used as a performance advantage? Or for betting?

I’m not entirely sure this is the best example, but one thing I do know is that not very long ago, in order to run this calculation you’d have needed a whole team of statisticians. Now you can more or less access this with the paid tier of GPT-4 (£16/month).

Something about this then starts to feel personal. Akin to the way any musician can play a song from sheet music, but there’s a personal signature to how a virtuoso pianist recites the same piece - instantly recognisable while still playing the same notes, at the same time, as an amateur.

Some athlete bodies and collective bargaining agreements have gone some way to stipulating athlete ownership, such as the NFL and NBA, they have limited this to cover only data directly collected by approved sensors - i.e. those the athlete wears (Obviously sensitive, personal data). But remain quiet on interpretation of this in relation to all other publicly available data.

As an individual athlete, your better funded competitor could know more about how you play than you do. Should the athlete have control, if not ownership, over how and where that data is used? This one is a grey area and needs long-term considered oversight and governance.

The question is… by who?

Who decides what data can be used and where?

During the Sports Technology Association debate, John Inverdale posed this exact question to the audience.

Who possibly could decide on how data gets used in sport? There are clear misaligned incentives for data ownership if overseen by a federation or governing body, and leaving individual athlete collective bargaining organisations to decide could also swing things too far the other way.

What would be needed is a clear, transparent and standardised framework. If every sport has a different approach, it stands to leave some athletes that are not so well represented (for example, ALL olympic athletes who have no collective bargaining whatsoever) worse off, and others kneecapping the commercial or operational opportunities for the very sport they play’s economic survival.

The only solution in my mind is a new independent, international and cross-sport agency whose sole mission is to set the gold standard for data use. But we need a name… something that speaks our global ambition, athletes and data… how about World Athlete Data Association? (WADA’s not already in use right? Oh.)

A new type of WADA that’s not WADA

Independent sports governance acronym jokes aside, the WADA model as I see it is the only way to set a clear set of guidelines for governing bodies to opt in to in a trustworthy manner.

WADA has many (very many) a problem, but imagine a world in which it didn’t exist. Some sports, even similar ones, could have completely done away with anti-doping at all, while others could’ve become overly draconian (remember coffee was a banned substance in sport until 2004 and is still on a ‘watch-list’).

For all its faults, enjoying sport would be a great deal harder than it is already without WADA.

Data usage in sports needs a coordinated approach. WADA uses the word harmonise, and I think that is appropriate here. This new entity would be tasked with drawing a line somewhere, and organisations would be incentivised to align with this harmonisation by their athletes, their brand partners and fans.

It will be expensive, complicated and slow to create this. But the alternative, i.e. not doing anything in an across the board manner, is far worse.

Athletes may not always demand ownership, but they should demand equity.

Where a global independent data use authority would differ from WADA is the addition of a commercial aspect to the value of their work, not just maintaining integrity.

Legally speaking it’s entirely clear that there will be myriad data use cases where an athlete is not the legal owner of the data. If an organisation has pioneered and invested in the research and development of a certain technology, and only they can feasibly capture this data, they will have no problem winning a legal battle over ownership.

That doesn’t mean it’s right. But in a legal precedent sense, it is clear.

What should happen, however, if a new independent data association were to exist, is that athletes need to not only have a say in what or how that data is used after capture, but crucially also share in the commercial upside of this data.

In their report ‘Hyperquantified Athlete’, Deloitte wrote

In this era of the hyper-quantified athlete, the increasingly urgent question is how to get from data collection (which is easy) to actionable insight (which is hard) to potential monetisation (which is really hard)-all the while protecting athletes rights, ensuring fair play and competitiveness and meeting the financial needs of leagues, players and owners

Monetisation, and who are the beneficiaries of the spoils, is the most important piece of the puzzle.

Just as a musician can choose to continue to by default receive royalties for the use of their work, or if lucky enough, choose sell the rights to the work in return for upfront cash (Justin Bieber sold a portion of his catalog to Blackstone in 2022.) Athletes should demand commercial upside if that data creates value for somebody, somewhere in the sports food chain.

And data will create value, with the market for for sports analytics predicted to reach $22.3bn by 2030.

Why do we care?

There’s two strands to think about here:

Because it’s the right thing to do

I don’t think it’s too simplistic to be very concise here - athletes should have a majority stake in the data they create. While there are absolutely salient arguments and nuances, if we take an Occam’s Razor approach, of course an athlete should have the ultimate say and/or reward in the use of their data.

So new is this paradigm, many existing athlete contracts don’t even cover consent relevant to this new dynamic at all. (Project Red Card being a higher profile example of a legal case being prepared around this)

Because as fans, we have a desire to quantify greatness

There’s clear and obvious needs to collect data if you are in the performance side of sport. But outside of performance, why does it matter? Why do we care about seeing athlete data at all?

In theory the joy of sport is in the drama and jeopardy, not in the underlying analytics comprising victory or defeat.

I think our desire for data in sport speaks to a deeper need to actually understand sportspeople. Data allows us, as fans, to attempt to codify seemingly unattainable greatness.

There’s something that I can never get over when watching a sporting great perform under pressure, I just for the life of me cannot believe they are actually able to do such a thing. (And I think this even when I watch my own Olympic performance… did I REALLY do that?)

How on earth could Messi, in his final chance to win a World Cup, with so much legacy resting on a single moment of absolute knife-edge jeopardy, watched by ONE AND A HALF BILLION people, have the gall to saunter up and merely suggest to the ball that it might be beneficial to just pop over to the bottom left in advance of the keeper arriving? It’s astonishing.

This sort of other worldly act is nonsensical. So I can’t help but crave some sort of scientific explanation through data.

Tell me that he had greater agility and a lower centre of gravity such that he was able to conserve energy allowing him the physiological headroom to take such a risk. Tell me his proprioceptive ability to control the minutiae of the complicated anatomy of the foot allowed him to know with 100% certainty he wouldn’t miss.

Tell me anything that helps me understand!

But no data will. That’s why sport is still in such high demand and will continue to do so - greatness in sport may actually be outside the realm of data collection. But, damn that doesn’t mean I don’t want to try find it - more data please! (With athletes correctly consulted and remunerated, obvs)

So what now?

In technology (bar supersonic commercial aircraft), once the genie is out of the bottle, there’s no going back.

Some would, quite often correctly, argue that data and statistics are draining sport of what makes it exciting. But whatever your opinion, we absolutely will not see sport go backwards in terms of use of technology and data.

What we will see, however, is sporting properties continuing to explore new ways to add value to fans and look to monetise their assets, including the data their athletes produce.

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to see the other side of the argument here, and I while I am diplomatically sympathetic to that point of view - my opinion is undeterred.

There has been some great progress made my unions and collective agreements around the world, but unless we can see a harmonised, sport-agnostic approach to governance, it’s the athletes who will ultimately lose out.

Legal precedent may set some groundwork, but one thing is for certain - the data an athlete produces should be the athletes IP. Some may choose to forego upside from this IP or sell the rights, but if an athlete creates it, they are the majority stakeholder on the data cap table.

Anything you’d love me to write up? Let me know.

Until next time, whenever that may be, farewell.